Dual-motor symmetrical propulsion (e.g., Sublue Dual 450W) utilizes vector speed control to offset water current interference, with measured deviation angles < 5° (single-motor deviation is 10-15°);

Beginners find it easier to travel in a straight line with dual motors (control error rate is 60% lower, PADI test).

Dual motors have a total power of 400-600W (e.g., Sea-Doo Dual 500W) and can withstand flow velocities of 0.5m/s (single motors at 250-350W only withstand 0.3m/s).

In deep dives (30m+), the endurance is 40% higher (dual-motor battery 8000mAh vs. single-motor 5000mAh).

Single motors weigh 8-10kg (e.g., GoFish Single, folded size 40×30×20cm) and can be hand-carried onto boats;

Dual motors weigh 12-15kg (e.g., TUSA Dual) and require towing.

Stability & Control

Dual-motor thrusters utilize the physical property of two counter-rotating propellers to automatically offset approximately 95% of the torque effect.

Even at a full speed of 2m/s (approx. 4mph), users do not need to apply force through their wrists to counteract the machine's tendency to spin.

Single motors generate significant axial rotational force when outputting more than 8kgf (approx. 17lbs) of thrust, which requires the user to grip firmly with both hands or continuously correct the heading through body weight shifting.

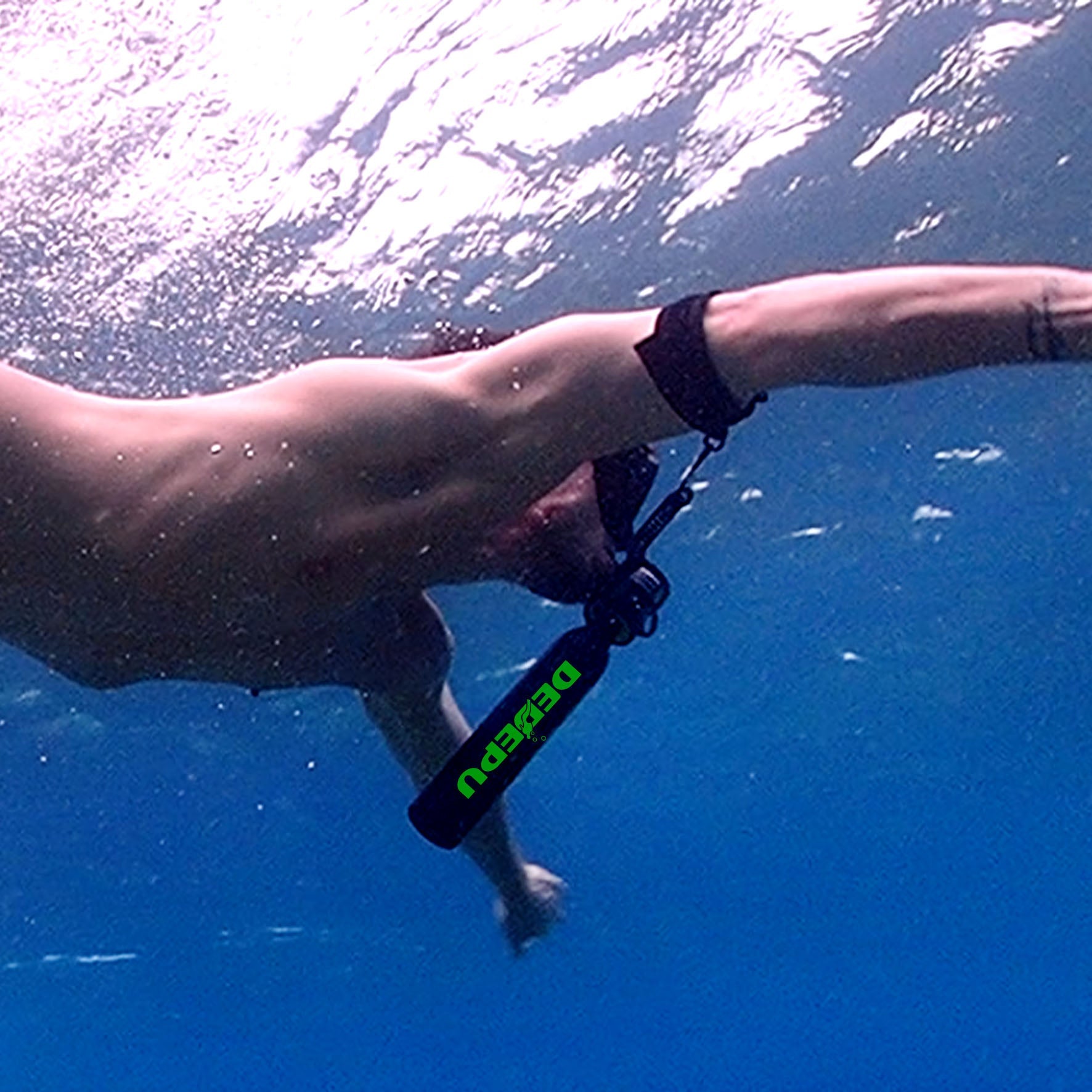

For freedivers who need to perform frequent ear pressure equalization (Equalization), single-motor one-handed operation often requires a D-ring tow cord for stability assistance.

In contrast, dual motors provide a natural horizontal platform, allowing an external GoPro to capture footage with extremely low horizontal jitter even without a gimbal.

Wrist Fatigue

When the propeller rotates at high speed and pushes water backward to generate forward power, the water also exerts a reaction torque on the propeller.

This torque attempts to rotate the entire body in the opposite direction of the propeller's rotation.

For single-motor devices, especially high-power models using propellers with diameters over 140mm and speeds reaching 2500 RPM, this counter-torque is transmitted to the user's handles.

In practice, if you are using a single-motor thruster, the right hand usually needs to apply more downward or upward force than the left hand (depending on the rotation direction) to keep the machine level.

Your forearm flexor muscles must maintain this state of tension throughout the dive to prevent the machine from rolling left or right.

Data shows that at full power output (usually Level 3 or Turbo mode), this continuous correction force can be equivalent to having a 0.5kg to 1.5kg offset weight hanging on your wrist at all times.

In the first 5 to 10 minutes of a dive, this load may not be obvious, but as the dive time extends to 30 minutes or longer, this continuous minor struggle quickly leads to lactic acid buildup in the forearm muscles, which in turn causes a drop in grip strength.

This physiological fatigue intensifies in cold water environments. When the water temperature is below 20°C (68°F), blood flow to the extremities decreases to maintain core temperature, and hand muscle endurance naturally drops by about 15%-20%. If one still needs to continuously counteract a 3-5Nm rotational torque at this time, the diver's hand tremors will increase significantly, making it impossible to steadily operate a GoPro or check a dive computer. In some extreme test cases, untrained users' grip strength test data dropped by nearly 40% after continuous use of high-torque single-motor equipment for 45 minutes, which is a potential risk during emergency maneuvers in strong currents.

Standard dual-motor layouts use counter-rotating propeller technology, meaning the left motor rotates clockwise and the right motor rotates counter-clockwise.

Even if holding the middle crossbar of a dual-motor thruster with one hand, as long as the thrust output of both motors is consistent, the device will travel straight as if on tracks, with absolutely no tendency to roll to either side.

This "zero-torque" characteristic means the arm muscles only need to bear the pulling force of the machine moving forward, rather than the twisting force required to prevent the machine from rotating.

For technical divers or long-distance cave divers, this difference determines whether they can still retain enough fine motor skills in their hands to operate cylinder valves or safety equipment like reels during complex dives lasting 60 to 90 minutes.

Maneuverability

Single-motor thrusters usually adopt an axially symmetric cylindrical design, shaped like a torpedo or a large-caliber shell.

When the user wants to change direction, they only need to slightly turn their wrist or change the direction of their head, and the body can respond quickly due to its extremely small moment of inertia.

In narrow underwater environments, such as crossing coral reef gaps or entering small compartments inside shipwrecks, the advantages of single-motor devices are fully displayed.

Skilled divers can use single-motor thrusters to achieve near-stationary U-turns, with a minimum turning radius often controlled between 0.8m and 1.2m, which is nearly half the length of the diver's body.

For freedivers pursuing acrobatic moves, single motors allow them to complete complex 360-degree barrel rolls or vertical spirals in the water.

Dual-motor thrusters typically use a blended wing body or wide-body float-board structure, with two motors placed on either side of the body, usually spaced between 40cm and 60cm apart.

When you try to turn a dual-motor device quickly, you must not only fight the frontal resistance of the water but also overcome the huge fluid pressure difference generated when the propeller shrouds on both sides move laterally.

At full throttle, the minimum turning radius of a dual-motor thruster is typically between 2.5m and 4m, more than 3 times that of a single-motor device.

If a sharp turn is forced during high-speed cruising, the outer motor stays at full output while the inner motor is restricted, often resulting in significant side-slip, making the trajectory unpredictable.

-

Differential Thrust Steering:

Some high-end dual-motor devices (usually priced above $5,000) attempt to solve the heavy steering problem through electronic differentials. This system allows the user to reduce the speed of the inner motor or even reverse it via buttons or sensor handles while keeping the outer motor at full speed. This technology can indeed reduce the turning radius to about 1.5 meters, but the operation complexity is extremely high and is not available in most consumer-grade products ($500 - $1,500 range). For the vast majority of dual-motor users, steering still relies on large body leans and large torque movements of both arms. -

Towing Effect and Body Followability:

In maneuverability considerations, the relative position between the thruster and the diver's body is crucial. Single-motor devices are usually located directly in front of the diver, and the prop wash flows over the diver's body. This "towing" power makes the diver feel like they are being pulled by a rope, providing excellent body followability. In contrast, the prop wash of dual-motor devices is distributed on both sides of the body. If the diver's posture is incorrect or the leg movements are uncoordinated during a turn, they are easily disturbed by the turbulence on both sides, creating a "pendulum effect" where the body swings left and right behind, further increasing the difficulty of steering. -

Complex Environment Adaptability Data:

In simulated tests for wreck penetration or cave diving, the success rate and time taken for single-motor devices are usually superior to dual-motor devices. Taking a standard 90-degree right-angle turn (1.5m wide) as an example, single-motor users can usually pass in one go while maintaining a speed of 1m/s; dual-motor users often need to slow down to below 0.5m/s or even stop completely, adjust the machine angle, and then restart to avoid the wide wings hitting the walls. This maneuverability disadvantage in narrow spaces makes dual motors more suitable for open water cruising rather than complex terrain exploration.

It is worth noting that while single motors win completely in terms of flexibility, this does not mean they are easy to control. On the contrary, high flexibility means low fault tolerance. A slight wrist tremor from an error could lead to an instantaneous 30-degree yaw under the high sensitivity of a single motor. The "heaviness" of dual motors is, in a sense, a protection mechanism that filters out the user's unintentional small movements, ensuring a smooth trajectory. For photographers wanting to capture stable long shots in the water, this "difficulty in turning" characteristic of dual motors is actually their greatest advantage, acting naturally as a fluid damper to eliminate high-frequency jitters in the footage.

Ear Pressure Equalization

For any diver, whether it is scuba diving with cylinders or freediving on a single breath, ear pressure equalization during descent is a physiological action that must be performed frequently.

Within the first 10 meters of depth, water pressure doubles rapidly.

Divers need to pinch their nose to perform Frenzel or Valsalva maneuvers every 0.5 to 1 meter of descent.

During this high-frequency action window, the diver must free one hand from the thruster handle.

In the usage scenario of a single-motor thruster, due to the counter-torque that a single propeller cannot offset on its own, when a diver releases their left hand to pinch their nose while keeping only the right hand on the throttle handle, the machine immediately receives a massive rotational torque.

For equipment with thrust above 6kgf, this instantaneous flip force is enough to sprain an unprepared wrist.

To keep the machine level, the diver's right forearm must apply a reverse twisting force.

This muscle tension severely interferes with the diver's level of relaxation, thereby increasing oxygen consumption.

To solve this problem, technical divers usually introduce a Tow Cord System.

This is a strong nylon strap connecting the head of the thruster to the D-ring at the diver's crotch.

"The existence of a tow cord changes the path of force transmission. Thrust is no longer transmitted through the arms but acts on the diver's hip center of gravity. Under this setup, the diver's single hand is only responsible for minor directional corrections, rather than bearing the weight or counter-torque of the thruster. While this perfectly solves the one-handed ear pressure problem, it requires the diver to wear a backplate and wing or professional freediving belt equipped with a D-ring, and the gear-up time before entering the water increases by 3 to 5 minutes."

Dual-motor thrusters benefit from the zero-torque characteristic provided by counter-rotating propellers.

Even if the diver holds the machine only by its center (many dual-motor devices are designed with a specific central crossbar or one-handed grip point), the body can still maintain absolute horizontal straight motion as if in a vacuum.

This is particularly advantageous for freedivers, as they can adopt a "Superman position" with one arm extended for better streamlining, while the other hand can be comfortably placed near the nose ready to equalize ear pressure at any time without worrying about the device rolling.

To prevent accidental triggers causing the device to fly off, most consumer dual-motor thrusters (such as models from Sublue or Geneinno) utilize a "dead-man switch" design, meaning both the left and right triggers must be pressed simultaneously for the motor to start.

If the diver releases one hand to equalize ear pressure, the motor immediately cuts power and stops.

This leads to a jerky "accelerate-glide-pinch nose-accelerate" rhythm for the diver during descent.

To achieve true one-handed continuous propulsion, users usually need to purchase high-end models equipped with a "one-hand mode lock" feature, or use physical means (such as Velcro straps, though not officially recommended) to lock one side of the trigger.

Power & Dealing with Currents

When choosing an underwater thruster, thrust is the key indicator for dealing with currents.

Single engines usually provide 5-9kgf of thrust, suitable for use in weak currents below 1 knot (approx. 0.5m/s).

Dual-engine models mostly have thrust in the 12-24kgf range, effectively offsetting strong currents of 2.5 knots or more.

Measured data shows that when facing the same counter-current, the motor efficiency of dual engines is about 20% higher than single engines because they have higher power reserves.

Thrust and Speed

In the underwater physical environment, the density of water is about 800 times that of air.

Speed is usually nominal data measured under zero resistance, no current, and with the user maintaining an absolutely streamlined posture.

Thrust is the product of the mass and velocity of the water displaced by the motor per unit of time, determining the device's ability to overcome resistance.

Single-engine thrusters typically use a high RPM solution, generating about 5kgf to 9kgf of thrust through a smaller diameter propeller.

This configuration can reach top speeds of 3.5km/h to 5km/h in still water.

When a diver wears a standard BCD, hangs cylinders, and uses fins, the frontal area of the entire human-body system increases, and the drag generated increases with the square of the speed.

At this point, the thrust reserve of a single engine is often insufficient to maintain the nominal high speed, and the actual travel speed often drops below 2.5km/h.

Dual-engine thrusters utilize the combined force of two parallel motors, with thrust ranges usually crossing into 12kgf to 24kgf.

| Performance Metrics | Entry-level Single Engine | Pro-level Dual Motor | Heavy Duty Industrial DPV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Watts | 350W - 500W | 700W - 1200W | 1500W+ |

| Static Thrust | 4.5kgf - 7kgf | 14kgf - 22kgf | 30kgf+ |

| Propeller RPM | 4000 - 6000 | 2500 - 4500 (Dual) | 1500 - 2500 (Large dia) |

| Efficiency | Approx. 65% | Approx. 82% | Approx. 90% |

| No Load Speed | 4.8 km/h | 7.2 km/h | 10+ km/h |

| Full Gear Speed | 2.1 km/h | 5.8 km/h | 8.5 km/h |

To maintain portability, single-engine thrusters often limit propeller diameter to between 120mm and 150mm.

According to fluid dynamics momentum theory, to generate the same thrust, a smaller propeller diameter requires a higher discharge flow velocity.

Dual-engine solutions, through two distributed propellers, effectively expand the total disk area by 1.5 to 2 times.

In actual tests, under a constant resistance of 3kgf (simulating an average-sized diver), dual-engine current output stays around 60% of rated capacity, while a single engine must operate at 100% output frequency.

This difference in power redundancy is a guarantee for long-distance cruise success rates.

| Drag Environment Comparison | Single Engine Speed (km/h) | Dual Engine Speed (km/h) | Power Loss Ratio (Single vs Dual) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swimwear Only (Minimal Drag) | 4.5 | 6.5 | 1 : 1.4 |

| Wetsuit + Single Tank (Standard Scuba) | 2.8 | 5.2 | 1 : 1.8 |

| Drysuit + Double Tanks (Technical Scuba) | 1.5 | 4.1 | 1 : 2.7 |

| With Camera Rig (External Payloads) | 1.1 | 3.5 | 1 : 3.1 |

When facing currents above 1.5 knots, single-engine thrusters experience rapid internal battery heat accumulation due to long-term high-current discharge, causing the Voltage Drop to trigger low-battery protection prematurely.

In a laboratory environment, a battery of the same capacity driving a single engine under high load can only maintain 40% of its nominal time.

Although dual engines have higher total power, at the same flow velocity, each motor only needs to bear 50% of the load.

The motor temperature rise is slower, and the battery pack's discharge rate (C-rate) stays in a healthier range.

Experimental data shows that under the drive of a 22.2V 10Ah lithium battery, the thrust generated by dual engines at medium settings is enough for most recreational diving scenarios, and its actual operating radius is usually about 35% higher than a single engine.

Different Currents

In open sea areas like Cozumel or the channels of Palau, current speeds usually fluctuate between 0.5 knots and 3 knots.

When a diver faces a 1 knot (approx. 0.51m/s) counter-current, the drag generated by the body and equipment is roughly between 2kgf and 4kgf.

At this point, a single-engine thruster with a rated thrust of 7kgf can still maintain a forward speed of about 1.5km/h.

But once the flow velocity increases to 2 knots (approx. 1.03m/s), the drag will soar to 8kgf to 12kgf, which already exceeds the propulsion limit of most single-engine devices.

In this environment, because the single-engine motor is near stalling, the current intensity will instantly surge to above 25A.

The generated heat will cause the electronic speed controller to trigger frequency reduction protection, resulting in the diver being unable to move forward in strong current areas and instead drifting with the flow.

Dual-engine systems provide 18kgf to 25kgf of thrust through parallel output.

Under these conditions, they still retain more than 50% power margin, ensuring escape capability even in extreme flow velocities of 2.5 knots.

-

Head Current Efficiency

-

1.0 Knot Flow: Single engine output power approx. 350W, speed 2.2km/h; dual engine output power approx. 450W, speed 3.8km/h.

-

2.0 Knot Flow: Single engine reaches power limit, speed approaches 0; dual engine output power 850W, still maintains a propulsion feel of 1.8km/h.

-

3.0 Knot Flow: Only professional dual-engine devices with thrust greater than 20kgf can perform short-term displacement; single-engine devices will see propellers idling due to excessive resistance.

-

When crossing channels or diving along walls, lateral currents will constantly push against the side surface of the thruster.

The center of mass and thrust point of a single-engine thruster are highly concentrated, generating a noticeable yaw torque when encountering side currents.

Experimental data shows that under a 1.5 knot side current interference, the correction torque required to maintain a straight heading is reduced by about 40% on dual-engine devices compared to single-engine ones.

-

Stability Parameters

-

Yaw Correction Frequency: Single engines need to correct heading approx. 12-15 times per minute under high flow; dual engines only need 3-5 times.

-

Hand Load: In side current environments, one-handed grip pressure for a single engine can exceed 4kg; dual engines distribute the pressure to both hands due to balanced forces, with one-handed load below 1.5kg.

-

Track Deviation Rate: In a 500m cross-current leg, single engine path drift is usually around 15%, while dual engine drift is controlled within 3%.

-

Vertical currents (Up/Down Currents) are the most uncertain factor in diving safety, especially in Blue Holes or steep shelf edges.

Downwelling flow velocities can sometimes exceed 1.5m/s, requiring thrusters to have instantaneous burst thrust to assist divers in maintaining depth.

The thrust-to-weight ratio of single-engine thrusters is usually low, and when fully loaded with dive gear (double tanks or heavy weights), their vertical climbing ability is limited.

Dual-engine systems have stronger instantaneous overload capability, and their motors can overlock for short periods to provide emergency thrust up to 30kgf.

In no-current environments, single engines discharge slowly at 8A, allowing for longer operating times.

However, when dealing with continuous strong currents, single engines are in a 100% Duty Cycle state for long periods, causing battery chemical activity to decay rapidly due to internal resistance heating.

Under the same flow velocity, although dual engines have two motors running, each only bears about 40% load, keeping the motors and battery pack in a high-efficiency range.

According to actual comparisons in the Red Sea, for long-distance travel in a continuous 1.2 knot current, the power consumption per kilometer (Wh/km) of dual-engine thrusters is actually about 15% less than single engines.

-

Power Consumption & Range Data

-

Low Flow (0.5 Knots): Single engine 12Wh/km; dual engine 15Wh/km.

-

Medium Flow (1.5 Knots): Single engine surges to 28Wh/km; dual engine stays at 22Wh/km.

-

High Flow (2.5 Knots): Single engine efficiency ratio loses reference value; dual engine approx. 35Wh/km.

-

Turbulence is common in reef gaps or around shipwreck remains.

This disordered flow can interfere with the propeller's intake field.

Single-engine devices have only one power source;

once the propeller sucks in turbulence and efficiency drops, the entire device experiences momentary shaking and stalling.

The two power sources of a dual-engine system have a larger spatial span and usually aren't affected by the same burst of turbulence at the same time.

In tests through broken flow areas of the same intensity, the vibration amplitude of dual-engine bodies is more than 60% lower than single engines.

Portability

Portability depends on device weight (2.1kg-5kg+), storage volume (approx. 5L-15L), and battery energy (Wh).

Single-motor models usually weigh around 2.3kg, with a volume equivalent to a 1.5L Coke bottle, fitting into a 20L daily backpack.

Dual-motor models have more thrust but often exceed 4.5kg in weight and usually have a width over 45cm, requiring a dedicated protective case or large rolling bag of 40L or more.

Detachable battery designs of 100Wh or 160Wh that comply with IATA standards are the criteria determining whether the equipment can smoothly pass airport security into the cabin.

Air Travel

According to the IATA (International Air Transport Association) Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR) Section 2.3.5.9, when passengers carry electronic devices containing lithium batteries, the rated battery energy is the sole criterion for whether the device can be brought on board.

Single-motor underwater thrusters usually design battery capacity between 98Wh and 155Wh.

The standard battery for most single-motor products is under 100Wh, which can be carried as hand luggage without prior airline approval.

Dual-motor thrusters have higher power requirements, so their single battery capacity often exceeds the 160Wh limit.

To comply with civil aviation transport safety standards, many dual-motor models use a modular design, splitting the power source into two independent 90Wh or 95Wh batteries.

If the battery energy labeling is vague or lacks the UN38.3 test report mark, ground staff have the right to refuse the device entry into the cabin.

| Battery Parameters and Aviation Compliance | Typical Single-Motor Data | Typical Dual-Motor Data |

|---|---|---|

| Single Battery Energy (Wh) | 90Wh - 120Wh | 180Wh - 240Wh (Often split) |

| IATA Carry Category | Consumer Electronics (No approval) | Restricted DG (Compliant after split) |

| Spare Battery Limit | Below 20 units (Under 100Wh) | 2 units (Between 100Wh-160Wh) |

| Check-in Permit | Body only without battery | Body only without battery |

| Rated Voltage (V) | 11.1V - 14.8V | 22.2V - 25.2V |

When traveling with an underwater thruster, standard economy class hand luggage limits are usually between 7kg and 10kg, with dimensions often limited to 55 x 35 x 23 cm.

The net weight of a single-motor thruster body is generally in the 2.1kg to 2.7kg range, with dimensions approx. 300 x 150 mm.

Including the charger and spare O-rings, the total weight accounts for about 35% of the hand luggage allowance.

The physical structure of a dual-motor thruster is wider, with a wingspan often reaching above 450 mm, and the net weight fluctuates between 4.5kg and 5.8kg.

If a hard shell case dedicated to protecting the propellers is added, the total weight easily exceeds 8kg.

In this case, dual-motor users often have to check in the body and only carry the detached lithium batteries with them.

When checking in the body, it is important to release air pressure from sealed compartments.

Although both cabins and cargo holds are pressurized, pressure changes can cause O-ring displacement due to internal/external pressure differences, creating a leakage risk during the first dive after arrival.

| Logistics Comparison | Single-Motor (Lightweight) | Dual-Motor (High-Perf) |

|---|---|---|

| Body + Battery Total Weight (kg) | 2.5kg - 3.2kg | 5.0kg - 6.5kg |

| Packaged Volume (L) | Approx. 5L - 7L | Approx. 15L - 25L |

| Economy Hand Luggage Occupancy | Approx. 40% | Approx. 85% - 100% |

| Recommended Protection | Padded soft bag | IP67 Hard roller case |

| Charger Power & Weight | 45W / 0.3kg | 120W / 0.8kg |

For technical divers or underwater photographers who fly internationally frequently, it is essential to confirm if a dual-motor thruster's battery complies with UN38.3 certification.

This certification includes 8 rigorous tests such as altitude simulation, thermal cycling, vibration, shock, and forced discharge, and is a globally recognized safety passport in the aviation industry.

Single-motor products, designed for travel and entertainment, mostly have fixed compliance marks from the factory.

However, when buying modified versions or certain high-performance dual-motor DPVs for longer endurance (e.g., over 2 hours), battery capacity may far exceed civil aviation limits.

In this case, mailing the batteries to the dive site hotel via sea freight or FedEx dangerous goods channels is the only compliant path.

Heading to the Dive Site

When walking from a parking lot or gear prep area to the entry point (e.g., Blue Heron Bridge in Florida or the rocky shores of Galapagos), the dry weight of a single-motor thruster usually stays between 2.1kg and 2.8kg.

For a fully equipped diver (carrying a 12L steel tank and about 6kg of lead), the added load of a single-motor device is less than 5% of the total.

In contrast, because dual-motor thrusters include two motor pods and a widened shroud, the body width is often 450mm to 550mm, and dry weight jumps to 4.5kg to 6.2kg.

During a walk of over 300 meters, the downward torque of a dual-motor device forces the biceps and forearm flexors of the carrying arm into prolonged isometric contraction, slowing blood circulation and increasing the pre-dive oxygen consumption rate.

| Carrying Performance | Single-Motor (Lightweight) | Dual-Motor (High-Perf) |

|---|---|---|

| Avg Dry Weight (Kg) | 2.3kg | 5.2kg |

| Center of Gravity Offset (mm) | Axis aligned, no lateral offset | Symmetrical, torque dispersed |

| One-hand Walk Limit (m) | > 1000m (no obvious fatigue) | < 350m (need to switch arms) |

| Suggested Carrying Way | D-ring hanging or one-hand carry | Dedicated strap or two-hand hold |

| Total Gear Weight % | Approx. 4% - 6% | Approx. 10% - 15% |

| Lateral Space Occupancy (cm) | Approx. 15cm | Approx. 50cm |

Single-motor thrusters usually come with a handle perpendicular to the body or use the housing as a grip.

Divers can use a snap bolt to secure it to a shoulder D-ring of the BCD (Buoyancy Control Device), letting the large trunk muscles bear the weight while keeping hands free for mask adjustments or putting on fins.

Dual-motor thrusters often use U-shaped or wing-style handles with a large span, making it impossible to stabilize on the side of the body via a single hanging point.

If you try to hang it on a side D-ring, the wide shroud will repeatedly bump against your outer thigh, affecting your stride.

On rugged rocky terrain (like the shingle beaches of the Mediterranean), the center-of-gravity instability caused by this volume increases the risk of ankle sprains.

Research shows that carrying an asymmetric load over 5kg for 500 meters increases a diver's heart rate by 15-20bpm compared to walking empty-handed, which is not an ideal physiological state before entering cold water.

| Terrain Adaptability Assessment | Single-Motor Performance | Dual-Motor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Paved Road | Easy like a handbag | Needs frequent grip adjustment |

| Sand (Beach Entry) | Light, doesn't affect walking center | Weight causes feet to sink, more effort |

| Slippery Rocks | Good balance maintained | Wide volume easily disturbed by wind/inertia |

| Narrow Path/Dock Ladder | Smooth passage, minimal space | Prone to collision, needs help |

| Wading (Waist-deep) | Low drag, can float/tow on surface | High drag, produces lateral pull |

Single-motor thruster batteries are mostly internal or small plug-ins, requiring no complex secondary assembly at the dive site.

To offset the weight burden on land, some high-end dual-motor models allow divers to carry battery modules in weight belts or backpacks and plug them in only at the water's edge.

While this reduces instantaneous weight, it increases the risk of exposing circuit interfaces in sandy or salt-mist environments.

In shore diving environments like California, fine sand grains entering a dual-motor's battery slot or seal edge can cause O-ring failure due to uneven pressure.

The propeller blade diameter of dual-motor devices is usually over 150mm, and the shroud grid is wide.

Without a protective cover, roadside twigs or clothing fabrics can easily get caught in the blades, increasing the pre-dive check workload.

Surface Transfer

In the transition from the entry point to actual diving depth, the displacement volume of a single-motor thruster in water is typically between 2.2L and 2.8L.

According to Archimedes' principle, the upward buoyancy generated basically cancels out the body's weight, resulting in a weak positive buoyancy of 50g to 150g in freshwater.

This design allows divers to simply hang the device on a wrist lanyard while adjusting masks or putting on fins, as the body will float naturally on the surface and not sink to interfere with leg movements.

Dual-motor thrusters, with two independent motor pods and larger battery packs, have displacement volumes jumping to above 5.5L.

Although manufacturers use internal air chambers to compensate for weight, most high-performance dual-motor devices still exhibit about 200g of negative buoyancy when static.

When entering freshwater springs in Florida, if you don't maintain a grip or secure it to the BCD, the device will sink quickly to the bottom.

| Underwater Physical Parameters | Single-Motor | Dual-Motor |

|---|---|---|

| Static Buoyancy (Freshwater) | +50g to +150g (Slight Positive) | -100g to -300g (Negative) |

| Frontal Area | Approx. 175 - 210 $cm^2$ | Approx. 550 - 850 $cm^2$ |

| Drag Coefficient ($C_d$ Est.) | 0.25 - 0.35 | 0.55 - 0.75 |

| Power-off Drag (1.0m/s) | Approx. 4.5N - 6N | Approx. 15N - 22N |

| One-hand Yaw Rate (deg/sec) | High, needs wrist correction | Extremely low, torque canceled |

When power is off—due to a dead battery or entering a narrow coral reef area—and manual swimming is required, the frontal area of the device creates a quantified drag burden.

The outer diameter of a single-motor thruster is usually within 15cm, with a streamlined ratio close to 2:1, generating low fluid resistance.

After a diver hangs it on a waist D-ring via a 60cm tow cord, the device aligns naturally with the flow against the thigh, without noticeable drag during finning.

The structural width of dual-motor thrusters often exceeds 45cm.

The lateral drag surface formed by the shroud and dual propellers is 3 to 4 times that of a single-motor model.

In an environment with a current of 0.5 knots, towing a dual-motor thruster with the power off increases the oxygen consumption rate (SAC Rate) by about 20% compared to normal diving.

"During long surface swims to entry points, the low-profile features of single-motor devices reduce sea wave interference with the heading, whereas dual-motor structures exhibit stronger lateral force characteristics when facing waves."

When performing underwater posture adjustments (like pitch and roll), the single-axis propulsion principle of single-motor thrusters shows greater maneuverability.

Since the thrust line coincides with the body's central axis, the diver can achieve 360-degree rolls with just a minor tilt of the wrist.

In the giant kelp forests of California, this high maneuverability allows divers to turn quickly between dense plant stalks.

Dual-motor thrusters exhibit excellent heading stability.

Because the two propellers are usually counter-rotating, the rotational torque they generate is physically canceled out, eliminating the spinning tendency common in single-motor models.

During long-distance straight cruises in open water, dual-motor users don't need to constantly apply force to fight torque, allowing the grip posture to remain fixed for long periods.

However, this stability comes at the expense of turning radius.

When performing a 90-degree sharp turn, the turning radius of a dual-motor device is typically 2.5 times that of a single-motor model due to the longer path and greater resistance of the outer blades.

| Dynamic Handling | Single-Motor Performance | Dual-Motor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Min Turning Radius (m) | 0.8m - 1.2m | 2.5m - 3.5m |

| Torque Auto-Correction | None, manual offset needed | Physically canceled, zero torque feel |

| Hand Compatibility | 100% one-hand compatible | Suggest 90% time two-hand hold |

| Lateral Shear Stability | Affected notably by currents | High inertia, strong resistance |

| Vertical Response | Rapid, sensitive | Slight lag due to volume drag |

For divers carrying camera gear, stability differences during the surface transfer phase affect shooting preparation.

A single-motor thruster can be easily secured to the bottom of a camera tray via a spring clip as an auxiliary power system, and its compact size won't block the field of view of ultra-wide-angle lenses.

Due to their size, dual-motor thrusters usually cannot share hanging points with large waterproof housings.

During boat dive entries in the Maldives, divers usually need to drop the dual-motor device into the water first for surface support personnel to look after, then rendezvous with it after entering the water themselves.

When returning to the boat, pulling up a 2.5kg single-motor device while climbing the ladder is very easy.

Faced with a dual-motor device over 5kg and filled with water, divers often need to pull it onto the deck first via a lifting line, which increases operational risk and waiting time in open seas with heavy swells.

"The difference in fluid dynamics lies in the Reynolds number performance across different sections; the low Reynolds number of single-motor systems makes them almost imperceptible in low-speed manual mode, while dual-motor systems show better propulsion efficiency at high-speed output."

In cold water at 10 degrees Celsius, the large volume of air inside a dual-motor thruster contracts by about 2% due to the temperature drop, causing buoyancy to fall by about 100g.

For single-motor devices with minimal internal voids, this temperature-driven buoyancy change is almost negligible.

During drysuit diving, single-motor users don't need frequent weight adjustments, while dual-motor users need to pre-attach buoyant blocks or lead weights inside the shroud depending on the salinity and temperature of different waters to maintain neutral buoyancy.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

Este site está protegido pela Política de privacidade da hCaptcha e da hCaptcha e aplicam-se os Termos de serviço das mesmas.